We had another cemetery (and Declaration of Independence signer) to visit - this one had some very special history.

As tensions grew between the colonies and Great Britain in the 1770s, Virginia held a series of meetings to organize its protests against the mother country. In March of 1775, the Second Virginia Convention was held at the church at what was then called Henrico Parish Church. Patrick Henry, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Peyton Randolph and other prominent Virginians were delegates to the convention. Here, Patrick Henry embodied the spirit of the Revolution on March 23, 1775, with his famous words....."Give me liberty.....or give me death!"

St. John's Church is one of America's most important sites, where - swayed by Patrick Henry's powerful argument - the delegates made a decision that changed the course of history, lighting the spark of the War for Independence.

Oh no, the gate was closed - AND LOCKED!

We walked around the brick wall and couldn't find an opening so we could visit. But wait, what was this?

An elevator? Okay, let's give it a try.

I'd say that's the first - and probably the last - that we've found the only way inside a cemetery and church is by elevator. But it worked and we were there.

St. John's Episcopal Church, founded 1741

Patrick Henry gave his passionate speech here

First things first - find the grave of George Wythe.

George Wythe (1726-1806) was an American academic, scholar, and judge. The first of the seven signers of the Declaration of Independence from Virginia, Wythe served as one of Virginia's representatives to the Continental Congress and the Philadelphia Convention and served on a committee that established the convention's rules and procedures. He left the convention before signing the Constitution to tend to his dying wife. He was elected to the Virginia Ratifying Convention and helped ensure that his home state ratified the Constitution. Wythe taught and was a mentor to Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, Henry Clay, and other men who became American leaders.

I just love wandering around historic cemeteries.

Eliza Poe (nee Elizabeth Arnold (1787-1811) was an English actress and the mother of Edgar Allan Poe who was born in London in the spring of 1787. Her mother was a stage actress in London from 1791 to 1795 and it is thought that her father died in 1790. In 1795, Eliza and her mother sailed from England to Boston arriving in January, 1796. There Eliza debuted on stage at the age of nine only three months after her arrival in the United States. This is not the exact burial site but the memorial marks the general area.

This was interesting. I wish I knew the story as to why the wall looks to be just partially intact.

Alexander Whittaker was an English Anglican theologian who settled in Virginia in 1611 and established two churches near the Jamestown colony. He was also known as "The Apostle of Virginia" by contemporaries. He was a popular religious leader with both settlers and natives and was responsible for the baptism and conversion of Pochahontas two years after his arrival. She took the baptismal name "Rebecca". Whittaker accidentally drowned in c. 1616 while crossing the James River.

We had no idea there was a visitor center on the grounds. Unfortunately, it was closed but we learned that guided tours depart from the center and take place inside the church and explore the events in Virginia leading up to the Second Virginia Convention, Patrick Henry's famous speech, and his political career. Sorry we missed it :-(

The grounds are so beautiful - I especially love this picture.

At the turn of the 20th century, hand-painted advertisement adorned barns and commercial buildings across the nation. This ad for Uneeda Biscuit across the street from the church is one of the better preserved, and a great example of the craft from an advertising pioneer powerhouse.

Uneeda Biscuits were introduced in the 1890s as a product of the National Biscuit Company, now Nabisco. In those days, crackers were packaged, shipped, and stored in, and sold directly from large cracker barrels, where they were exposed to air and went stale quickly. Uneeda biscuits were lighter, flakier, and stayed crisper longer due to their packaging. In 1896, National Biscuit Company spent $1 million in a branding campaign to compete with Cracker Jack, a competitor of Uneeda Biscuits. The packaging featured a boy in a raincoat and has been considered one of the original consumer packaging concepts that did not rely on identity recognition. The boy in the raincoat signified the way the packaging kept moisture out of the product by using interfolded wax paper and cardboard. The Uneeda brand was discontinued by Nabisco in 2009.

But one more stop.

Since 1828, a small building currently known as the Jackson Death Site has stood south of the city of Fredericksburg, Virginia. The building was built not as a residence but as the office of the small farm of Fairfield. As a slave labor farm, the building may have served as office space for slave overseers.

Fairfield's close proximity to Guinea Station, a stop along the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad, ensured a steady flow of activity in the surrounding area throughout the Civil War. The wide variety of people who passed through this area sometimes refer to it under different names including Fairfield, Chandler Plantation, and Guinea Station.

Most famously, the Civil War brought Confederate General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson to Fairfield. In the lead-up to the Battle of Fredericksburg, Jackson's command camped in the area for a short time. But it was six months later, during the Battle of Chancellorsville, that Jackson would make the small office famous. After his wounding in a friendly fire incident and the amputation of his left arm, the survivors worked quickly to carry Jackson into friendly territory, eventually reaching the field hospital near Wilderness Tavern. Two days later an ambulance carried Jackson a distance of 27 miles to Guinea Station. Doctors hoped that Jackson would gain strength at Guinea and then proceed to Richmond by rail. However, Jackson developed symptoms of pneumonia and would never get on the train. He died in the farm office eight days after his wounding on May 10, 1863.

In the 1900s, private citizens sought to preserve the building in which Jackson died. The efforts served a larger goal to memorialize Confederates and control the story of the Civil War.

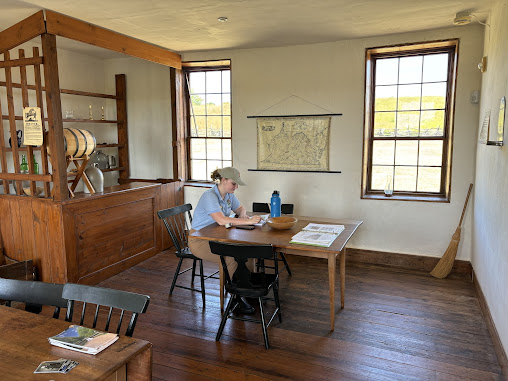

We stepped inside where a guide was explaining things to a small group of visitors.

Unfortunately, most of the original artifacts had been removed for the season due to the extreme heat.

Sadly, no bed in the room. :-(

This is the room used as a conference room and, later, a waiting room.

This marker is one of 10 similar small rectangular stone monuments commonly referred to as the Smith Markers because of the role that one of Jackson's former staff officers, James Power Smith, played in their placement. The markers identify important sites related to Robert E. Lee, his generals, and their actions from 1862-1864.

The effort to place these stones began in 1902 when Samuel B. Woods suggested the formation of a committee to mark important places on the battlefield. It was later described that the purpose was not to mark battlefields, or lines of battles, but certain points or locations that would be of lasting historic interest.

Smith directed the placement of the markers, including this one next to the farm office where Stonewall Jackson died. Placement was completed in 1903. Originally the marker was west of the house, near the rail line, so that it could be readily seen by train passengers. The National Park Service moved it to its current location in the 1960s. The Park Service added the last two lines of the inscription to prevent the misconception that the monument marked Jackson's grave.