The following day was just as long (or maybe longer) than the day before. First stop was the home of James Monroe.

James Monroe, 1758-1831

Encouraged by his close friend, Thomas Jefferson, Monroe purchased a deed for one thousand acres of land adjacent to Monticello (Thomas Jefferson's home) in 1793 from the Carter family. Six years later, Monroe moved his family onto the plantation where they resided for the next twenty-five years. In 1800, Monroe described his home as "One wooden dwelling house, the walls filled with brick...." Over the next 16 years, Monroe continued to add onto his home, adding stone cellars and a second story to the building. He also expanded his land holdings, which at their greatest included over 3,500 acres. However, by 1815 Monroe increasingly turned to selling his land to pay off debt. By 1825, he was forced to sell Highland completely.

Edwin Goodwin purchased the property for $20 per acre. And in 1834, Goodwin sold the house and six hundred acres and then it was sold again in 1837 to Alexander Garrett. Garrett gave the property its second name which remained with it to the present day "Ash Lawn". Over the course of the next 30 years, Ash Lawn-Highland was sold numerous times until 1867, when John Massey purchased it. It remained in the Massey family for the next 63 years. In that time period, the family added to the house, and it took on its present-day appearance.

Highland was sold for the last time in 1930 to Jay Winston Johns. The Johns family soon after opened the house to public tours and upon his death in 1974, Johns willed the property to James Monroe's alma mater, the College of William and Mary. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.

It was interesting to learn that the house that stands on the property today is not the original house.

The property today includes an 1818 guest house, an 1850s addition, and an 1870s Victorian style farmhouse, and a reconstructed three-bay slave quarter, gable-roofed ice house, gable-roofed overseer's cabin and a smokehouse.

In 2016 the name Ash Lawn-Highland was dropped and the house was redesignated James Monroe's Highland to more clearly communicate the relationship to the President. Today Highland is a 535 acre working farm, museum, and a performance site for arts, operated by the College of William and Mary.

Evidence that this home, long believed to be an original wing of Monroe's residence was, in fact, a guest house surfaced when archaeologists discovered foundations of a much larger home presumed to be Monroe's home. Additional evidence for the current residence being a guest house include construction techniques that post-date Monroe moving into his mansion at the end of 1799 and dating of the existing structure as being made from trees harvested between 1815 and 1818.Wing on the left original guest house

We went into the guest house - even shorty me had to duck.

Inside we saw some interesting artifacts.

Maria Hester Monroe, the younger daughter of James and Elizabeth Monroe, worked or "wrought" this sampler in 1814 when she was eleven years old - an age when a girl's formal education included needlework.

James Monroe

Monroe Presidential China

And outside there were some items of interest.

Iron casting of a mileage marker on Highway 40, the first federally supported interstate roadway, created during James Monroe's presidency. This marker was given by the state of Pennsylvania to Pennsylvania native Jay Winston Johnson, who initiated Highland's restoration in 1931.

Ron likes to see "Witness Trees" - those of historic landscapes that remain in place decades or even centuries after noteworthy events unfolded there. Often the trees were young when the event took place and have now grown to be massive, silent sentinels of history.

This is a White Oak that they estimate to be 350 years old.

And then it was time to move on about 90 minutes south to Appomattox, the site of the Confederate surrender on April 9, 1865.

After a long battle at Appomattox Courthouse, confederate desertions were mounting daily and by April 8 the Rebels were completely surrounded. Nonetheless, early on the morning of April 9, Confederate troops mounted a last-ditch offensive that was initially successful. However, soon the Confederates saw that they were hopelessly outnumbered by Union soldiers who had marched all night to cut off the Confederate advance.

Later that morning, Lee - cut off from all provisions and all support - famously declared that "there is nothing left me to do but to go and see Gen. Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths". But Lee also knew his remaining troops, numbering about 28,000, would quickly turn to pillaging the countryside in order to survive. With no remaining options, Lee sent a message to General Grant announcing his willingness to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia. The two met in the front parlor of the Wilmer McLean home at one o'clock that afternoon.

McLean House

The house became a sensation after the surrender and in 1893 it was dismantled for transport and display in Washington D.C. However, that display never happened and the National Park Service reconstructed the building on its original site in the 1940's. One of the guides related that a good portion of the house was removed by souvenir hunters in its dismantled state and when they reconstructed the house they could only partially utilize the original building materials. The bricks on the front of the building are all original.

Signing portrait

Lee asked for the terms of the surrender, and Grant hurriedly wrote them out. All officers and men were to be pardoned, and they would be sent home with their private property - most important to the men were the horses which could be used for a late spring planting. Officers would keep their side arms, and Lee's starving men would be given Union rations.

We were able to see a reproduction of the room.

The table and chair that Grant used - the originals are in the Smithsonian

The table and chair that Lee used - the original chair is in the Smithsonian

The vases on the fireplace mantle are the originals.

And the couch on the other side of the room is the original - Captain Robert Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln's son, sat here during the surrender.

We went to the back of the house.

As we walked back to the front, we stopped to speak with the National Park Volunteer, Drew. What an amazing young man he is. He will be a senior in the fall at DeSales University in Pennsylvania and is majoring in history. After serving the last two years as an intern at Fort McHenry near his hometown of Baltimore, he applied this year to work at Appomattox and was accepted. We had a great time talking with him and I was able to sneak in a picture.

As we left the house, we ran into another interesting man and stopped to talk. It was very hot that day and this veteran was waiting patiently under a tree for his family. Turns out he was once stationed in Washington State. He also served at one time on the USS Yorktown which, coincidentally, we had passed by on our way to Fort Sumter and Ron showed him a picture of her.

We saw a few interesting things in the Visitor's Center.

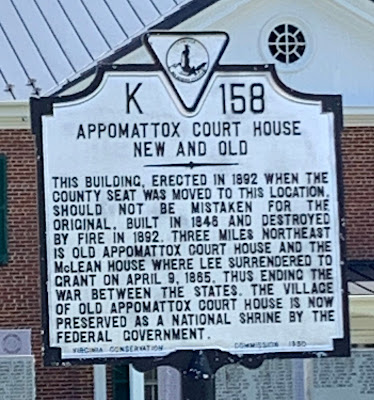

As we drove out of town we stopped to take a photo of the "new" Appomattox Court House.

What an amazing, historical day.

Don't those samplers amaze you? Done by young girls with no pre-packaged kit, I suppose. Just lovely. This sounds like another full day, but I love how you grab the opportunity to talk to guides and guests.

ReplyDeleteWe've met a few really interesting people along the way.

Delete